We are delighted that Lynda Kresge, one of the travelers on our recent Founders Trip to Uzbekistan has agreed to allow us to share some of her writings and photographs about her experience traveling in Uzbekistan with Exeter International. Lynda is a retired university librarian. She is happily spending as much time as she can these days researching and participating in travel adventures around the world.

The Beginning…

Uzbekistan! I am excited beyond words to be exploring this section of the ancient and fabled Silk Road (which runs for 7,500 miles between China and the Mediterranean). Traders, merchants, and pilgrims have traveled this route through the centuries, including, of course, Marco Polo in service of Kublai Khan.

The Silk Road passed through Khiva, Bhukara, and Samarkand, all places we will visit on this trip. It’s the stuff of exotic legends and brutal histories.

I am part of a group of 11, on an Exeter Founder’s trip with founder and guide Greg Tepper. The history of this part of the world is almost impossible to grasp — it is complicated, consequential, and labyrinthine.

Uzbekistan sits in the very middle of Central Asia, a doubly landlocked country wedged between Russia, China, and India. It is the central “Stan” of the region, bordered by Kazakhstan, Turkmenistan, Afghanistan, Tajikistan, and Kyrgyzstan. It is slightly larger than California, with a population of about 32 million.

First Stop, Tashkent

Tashkent started out as an oasis on the Chirchik River 2,000 years ago. (Tash means “stone” and Kent means “settlement.”) Today it is the capital of Uzbekistan and is its largest city. It was already a thriving city when it was completely destroyed by Genghis Khan in 1219. Seven centuries later, in 1966, it was flattened again, this time by a devastating earthquake. 300,000 people were left homeless. Somehow, within 3 1/2 years after that, a new Soviet Tashkent was built, much of it in typical concrete block style. It is now quite a mish-mash of restored 12th century mosques, classical Russian architecture, blocky buildings, and statues of workers with bulging biceps.

1. Visit to the Osman Koran

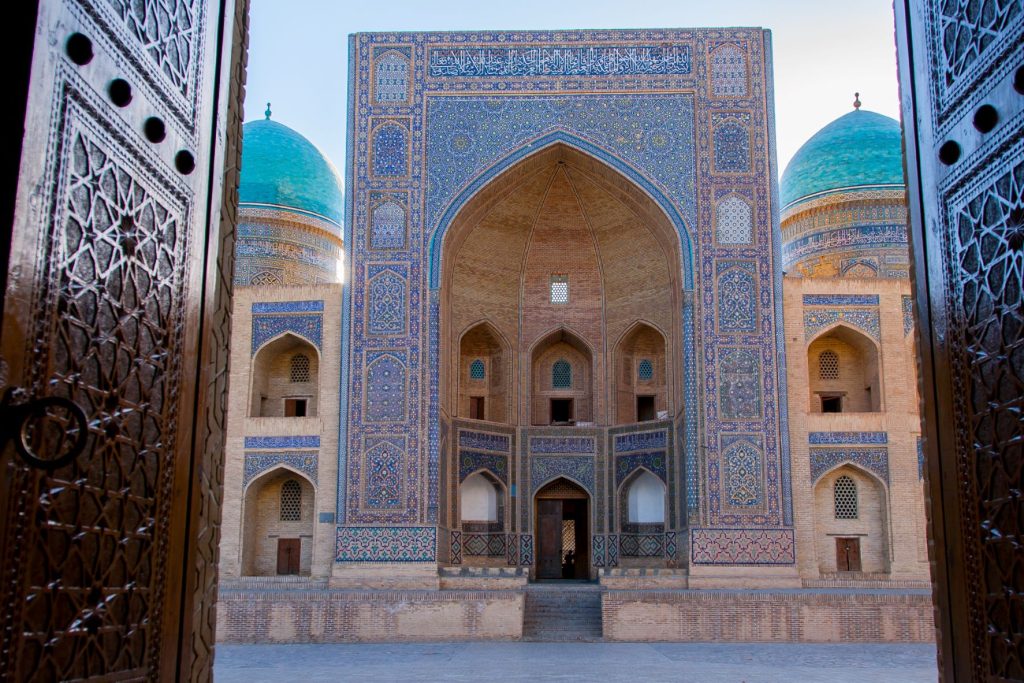

We start in Tashkent’s Old City, travelling back in time to the 16th century Barak Khan Madrassah, built by Barak Khan (“Lucky Ruler”), the grandson of Ulug Bek, who was himself the grandson of Tamerlane, Uzbekistan’s 14th century hero conqueror. The madrassah is made of brick, with three blue domes, decorated with tiles, mosaics, ivory, metals — a beautiful, squat symmetrical building with a huge portico. Some of the original tiles have been preserved to this day. Because it was built to educate only local boys, it has only one story — foregoing the usual student accommodations that would normally occupy a second floor. The 35 student study cells now provide space for craftsmen and souvenir vendors. It is a great way to introduce us to traditional Islamic architecture and scale.

In this same complex is the small Muyi Muborak Library, rich in ancient materials. And here we are given a private viewing of the famous, immense Osman Koran. Dating from 655, just 19 years after the death of Muhammad, and made of elk or deer skin (not vellum or parchment), it is believed to be the oldest copy of the Koran in the world. It is written in large Kufic script on 378 folios, each sheet about 21″x27″.

Tamerlane first brought this magnificent Koran to Samarkand in the 14th century; after that it traveled to St. Petersburg (seized by the Russians as a war prize in 1869), then to Ufa, and finally to Tashkent in 1924. It is priceless, kept in a glass case.

2. Uzbek Ceramic Experience

There are three famous schools of ceramics in Uzbekistan. We visited one tonight, belonging to Akbar Rakhimov of the Rakhimov family, third generation master ceramic artist. He works here in Tashkent with a son and daughter in a house that they have turned into a ceramics guesthouse, pottery school, potting studio, and gallery — a kind of museum school and ceramic shop. They accept only a handful of students, some as young as 6 years old!

The house resembles a Madrassah from the outside — but inside, the courtyard is a magical surprise: a stream; miniature bridges; fruit, date, almond and pomegranate trees; twinkling lights. Akbar’s father, Muhiddin, wrote the definitive scholarly book on Uzbek pottery, which has been translated into English through funding by UNESCO; his work is collected worldwide and held in many museums, including the Hermitage.

Akbar Rakhimov himself greeted us warmly, then moved to the background. We sat down to an Uzbek feast of delicious and colorful traditional dishes prepared by his wife and daughter and served in countless courses, while his son Alisher served as gracious host and taught us about Uzbek pottery; a musician played beautiful traditional music during the meal. The Rakhimovs have many pieces of ancient Uzbek pottery, which are on display in their studio, some dating back to the 9th century! They say that they are still studying and learning from these old examples.

Rakhimov makes exquisite ceramics, most of it traditional, but some experimental in design. They dig their clay from the nearby banks of the Chirchic River. Five years ago a law regulating air pollution in the city was put into affect and they had to move from wood to gas and electric kilns. This affected the way the clay fired, so they have just finished building a wood fired kiln 36 miles from town.

It was a lovely, fascinating, inspiring, delightful evening.

3. A Visit to the Chorsu Bazaar

Chorsu (“crossroads”) is the historical market in the square located on the southern edge of Tashkent’s old town. It is huge. 2.5 million people live in this city and I bet sometimes it seems as if they are all here at the same time. Bazaars have been the centers for trade, eating, and entertainment throughout the ages in Asia, and Chorsu follows this tradition; it holds a large collection of vendors under a complex of interrelated domes, all centered around a big blue dome (diameter 1,000 feet!) of 3 stories (serviced by an elevator) — built to protect both people and goods from the heat and dust. Mountains of spices, acres of fruits and vegetables, fresh meat, grain sacks practically the size of small cars, jewelry, clothing, carpets, food. It’s hard to find words to describe the sights at these markets. Bright colors, intense fragrances. Tashkent is famous for pecans, dates, apricots, pistachios — you will find them here in staggering abundance.

I am fascinated by all the gold teeth we see in smiles here. Have yet to get a really great shot of these but will keep trying. Am having fun with my little Instax camera (like an old Polaroid) — everyone from little kids to oldsters love getting an instant photo!

Onward To Nukus

4. A Visit to The Savitsky Museum in Nukus

The Savitsky Art Museum is a magnificent museum with an astonishing collection of priceless avant-garde Soviet art. It also houses one of the largest exhibitions of archaeological finds and folk art anywhere in Central Asia.

How this came to be is a kind of miracle in itself. The museum is the creation of a man named Igor Savitsky (born 1915) who spent his life collecting (at great personal risk) thousands of pieces of banned Russian art from the 1920s and 1930s, which he somehow managed to transport to this remote place without interference from either Moscow or the KGB. In the mid-1930s Stalinist socialist realism became the only acceptable form of Soviet art, so great numbers of beautiful creative pieces of modern art vanished practically overnight, either destroyed or hidden away. And the artists who resisted Stalin and stayed openly true to their art were executed, or imprisoned, or sent to mental institutions or to the gulag. Only a few returned from “rehabilitation.” Savitsky hunted down and rescued the art pieces that survived this tyranny one by one, found ways to buy or borrow them, and vowed to protect and preserve them. He opened his museum in 1966 and served as its first curator. An award-winning documentary from 2010, The Desert of Forbidden Art, tells the remarkable story of this man and his collection; it is available on Netflix. The following year the New York Times published a fascinating review.

The collection was, as promised, astonishing. The museum provided us with a charming young docent to guide us through the collections, and afterward served us a sumptuous tea in their conference room.

Above is a photo of one of my favorite artists in the museum, A.N. Volkov.

Onward to Khiva, Museum City

Legend has it that the well upon which Khiva was built was dug on the orders of Noah’s son, Shem. Its known origin dates to somewhere between the 5th and the 6th centuries B. C. — archaeological excavations in the 1980s and 1990s found signs of these early inhabitants as far as 21 feet below the current ground level. Today the old city is a protected city: it has been a World Heritage Site since 1990. You cannot buy property here — it has to be passed down through the family; and any proposed changes in your property must be submitted to UNESCO for permission.

Khiva has a long, colorful, barbaric history, full of warring factions, tribal massacres, and revenge. It has been destroyed and rebuilt seven times. First it was razed to rubble by a conquering Arab force in 709. Yet by the 9th century its population was estimated to be as high as 800,000. By the 10th century, the city was an oasis caravan town on the Silk Road, a powerful trading center. In 1220 it was sacked by Genghis Khan. Its subsequent rapid recovery is attributed to its reputation for craftsmanship in pottery and tile making. It was conquered again in 1505, and again in 1740 by Iran, followed by famines and plagues. By the 19th century the various tribal factions in the area had united, bringing a thriving trade business and great wealth.

Well into the 18th and early 19th centuries, Khiva featured a flourishing slave market. Thousands of captured Russians were sold in those years (a result of repeated failed Russian attempts at incursions). The last of them were finally freed in 1840 in an effort to stop Russian aggression by British envoy Lieutenant Richard Shakespeare, who negotiated to return all 419 of them to their homeland. Russia finally entered Khiva in 1875; the last Khan abdicated in 1920. And Khiva became part of the Uzbek SSR in 1924.

These complicated and brutal histories make my head hurt. It is the same for every city we will visit on this trip.

Our ride from Nukus to Khiva took us about 4 1/2 hours (284 km), through a sandy, arid countryside dominated at this time of year by desert sage plants and grazing livestock. Along the way we saw cattle, sheep, goats, and even a couple of camels in the fields.

5. Walking the City Walls in Khiva

We arrived in Khiva in time to take a sunset walk along the alleys inside these ancient city walls (the Ichan Kala). Parts of the wall date as far back as the 5th century; most however are from the 1600s. The earliest iterations of the wall once housed archers in turrets more than 60 feet high. Today the walls are up to 30 feet high and 25 feet thick. Guard rooms once stood on the north side where customs duties were collected from caravans arriving from Urgench; the south side was the arrival point for caravans from the Cassandra area; royal proclamations were announced from the east wall, where the gate marked the entrance to the slave market. Massive gates sealed the city from dusk to dawn, protecting it from raids and desert storms.

About 50,000 people live and work in Khiva today. The entire old town here is a little like a living museum, a kind of film set with preserved historic buildings. It is the most intact and most remote of Central Asia’s Silk Road cities. The shops close up at 5:30. The streets are not lit at night. Our hotel lies just outside the South Gate.

Dinner our first night was on a private terrace under the stars inside the Ichan Kala walls, in the old city. As we dined, the sun set, the air stayed balmy, and a crescent moon rose over the minarets nearby. It was like being in an Arabian Nights fairy tale.

6. Visiting a Silk Carpet Work-Shop in Khiva

Uzbekistan is the third-largest producer of silk, after India and China.

A short summary of silk making: the blind, flightless moth, Bombyx mori, lays 500 or more eggs in four to six days and dies soon after. The eggs are like pinpoints – one hundred of them weigh only one gram. From one ounce of eggs come about 30,000 worms which eat a ton of mulberry leaves and produce twelve pounds of raw silk.

Silk is warm and comfortable and it also possesses a unique luminescence and lustre that made it the queen of fabrics in China. Once it became popular in the West, demand skyrocketed and it became worth its weight in gold. Until 1924, the Khanate of Khiva was the only country outside China to use silk money — each note handwoven and then printed in the local mint. When the money got dirty, it was quite literally laundered! After 1924, when this part of the world was absorbed into the USSR, silk money was no longer legal tender. Instead, it became fashionable to stitch the silk notes together into robes and quilts.

Christopher Alexander (a Brit) founded the Khiva Silk Carpet Workshop in 2001 in a converted madrassah in Khiva’s old city, under the auspices of Operation Mercy and UNESCO. He and his designers found inspiration in the wooden door carvings and the tile patterns of the ancient city’s Khan fortress (Kunya Ark). They incorporated these traditional designs, and tried to recreate traditional natural dyes for the colors they found there, into their carpet weaving.

Time-honoured processes are highly valued here and are taught to younger apprentices. The environment of creativity and concentration, combined with the click-clack of the looms, is almost meditative. There is a pride too, in how natural everything is. Our tour guide calls our attention to a box of crushed pigments, nine different raw colors, each in a small bag. There is cochineal and madder root for red, dried pomegranate rind for gold, walnut husk for brown, indigo for blue.

In 2004 Christopher Alexander opened a suzani (embroidery) workshop nearby, a collaboration this time between Operation Mercy and the British Council. Here traditional designs are hand stitched with silk thread on cushion covers, wall hangings, napkins and table mats.

Suzani derives from the Persian word for needle. However, for textile lovers, the word is synonymous with the glories of Uzbek embroidery. Stitched cooperatively by women and girls for centuries as part of their dowries, suzanis today remain a significant decorative and cultural art in Uzbekistan.

7. A Visit to the Djuma Mosque in Khiva

There were once over 100 mosques in Khiva. The Djuma Mosque (Friday Mosque) is the oldest, built in the 10th century and rebuilt in the 18th. Since today is Monday, it is open to visitors.

It is dark and cool inside. A single large hall holds 218 carved wooden columns made of elm, which support the flat roof, 2 of which are originals, and 12 of which are still the originals from a restoration in 1789. One, remarkably, comes from India. It is like a petrified forest inside this mosque! Each column is fascinating in detail, unique in shape, size and pattern. Each is supported by a stone block, some of which are also carved. At each wooden base is a metal cuff stuffed with camel wool to absorb humidity, deter termites, and provide a little protection during earthquakes. Normally the focus of a mosque is the mihrab — the door which points toward Mecca — but in this place that door pales in comparison to the columns.

I do love this town, even though clearly some of the restorations serve expediency perhaps more than actual replication. It really is a fascinating, magical and supremely photogenic walled city of khans.

The photo above is of an old man who allowed me to take a polaroid. He was quite surprised by the whole idea and pleased by the gift of a photo. It turns out that he was one of the renovators of the old city here in Khiva. Very sweet man.

Onward to Bukhara

The journey from Khiva to Bukhara is a 10-hour road trip across the Kyzyl-Kim Desert (116,000 square miles). Luckily, we drive instead about a half-hour to the airport in Urgench, and take a 60-minute flight.

Bukhara is actually an oasis in that desert, a holy place and and one of the oldest cities in Central Asia, current population 1.5 million. Its name comes from the Sanskrit word for monastery (“vikhara”). It is believed to have been inhabited continuously from about 3,000 B.C. There are no mountains here. Water was more precious than gold in this oasis. Bukhara is a center for all handicrafts and is famous for its chefs. In addition, the strong mineral water in Bukhara is said to melt kidney stones, so the government has built health spas here.

Bukhara was taken by Alexander the Great in 329 B.C. and has changed hands many times since.

8. Exploring Jewish Bukhara

Bukhara once had a large Jewish community — in the 16th century, in fact, most of the Jews in Central Asia lived here. They had first arrived around 500 B.C., as captives of the Assyrians. As recently as a century ago, they had controlled the silk markets and knew the secret dyes which made the Bukhara rugs glow. When the Soviet Union collapsed, many of these Bukharan Jews migrated to Israel and the United States. Less than 500 Jews now live in all of Uzbekistan. In the the 1970s, 40,000 Jews lived in Bukhara alone; today, there are 360 from 50 families, many of them surviving on financial help from relatives in Israel and the USA (in New York City, Queens alone has 50,000). Bukhara no longer has a yeshiva to train those who wish to become rabbis, but the local Jewish community school (which teaches in Uzbek, Russian, English, and Hebrew) is known for its high educational standards, the most academically challenging in the city, and attracts students from the wider community. All students at the school are required to learn Hebrew.

We visit the Jewish Quarter and its old synagogue, down winding alleys in the old town. It dates from the 16th century, is still in use, and lies partially underground. It is over 425 years old and has a Torah that is 2,000 years old! Behind beautiful carved doors lies a white-washed courtyard decorated with Hebrew symbols. Services are held twice a week (Friday and Saturday).

Legend has it that the Prophet Job struck the arid ground of this region and a spring of water miraculously gushed forth, so we also visit the site known as Job’s Well (Chashmai Ayub). The city grew up around this site and was perhaps one reason for the city’s early Jewish settlements. The water from this well does not have the salinity of other water in this region and our guide did not have an explanation for this fact. But the water is believed to have special properties, and visitors bring bottles to collect water from the spigots. I now can say that I have washed my hands with water from Job’s Well.

9. Relaxing at Lyabi Khauz

I especially love the Bolo Hauz (hauz means pool) with its 20 pillars and lovely setting. This mosque is where the Emir would come to atone for his sins once a week. I can only imagine the security involved in that venture outside the Ark Fortress! Today, in a peaceful corner under the tall pillars, an artisan sat hammering patterns into brass plates.

The Lyabi Khauz, however, was the largest of the city reservoirs, fed from the main canal which still divides the old city. Professional water carriers used to deliver large leather bags of water from here to rich clients. Its steps date from 1620; its mulberry trees from 1477! I will let other sources describe it to you:

“The Lyab-i-Hauz is the modern center of traditional Uzbekistan. A place where the very soul of Central Asia lies mirrored in a piala (handleless teacup) of steaming green tea or in the reflected symmetry of a resplendent portal, where cloudy-eyed white-beards contemplate the march of time and take shelter from a land of transition.

The chaikhana (tea house) is not only a way of life in Central Asia, it is also an escape and an antidote to life in Central Asia. It is the essential lubricant to friendship, trade and travel. It’s professionals are a hard core of regular nine to fivers, equipped with personal teapots, pialas and backgammon sets and brandishing gleaming arrays of heroic Soviet medals. Many took part in World War II and are a wonderful source of local oral history. In few places does the name Churchill elicit such mad affection.” — Uzbekistan: the Golden Road to Samarkand, 2014.

10. Visiting the Ark In Bukhara

The oldest building in Bukhara, in the very core of the ancient city, is the massive Ark Fortress. It was built in the 5th century, and for over a millennium — until the takeover by the Russians in the 20th century — it was used as a royal residence and a fortress. By the 16th century it had grown to a complex of over 3,000 inhabitants, providing a palace, harem, thrown room, reception hall, office block, treasury, mosque, gold mint, dungeon and slave quarters. It was as much a prison as a residence for the Emir, who resided in isolation from the rest of his city. It was a place of secrecy and paranoia: “water was brought in from outside the Ark in skins guarded by armed officers, tasted twice by the attached bachique and only then resealed and despatched to the Emir. Food was likewise tasted by the Khosh Begi and his officers and, after more than an hour of close scrutiny, placed in a sealed box (to which only the prime minister and Emir had keys) and dispatched to the Emir… it is perhaps here, buried deep behind two city walls, wrapped in the imposing bastions of a fortress and concealed in a maze of bedrooms, that the root of the emirate’s introspection and isolation is most tangible.”

Today the Ark serves as the town’s main history museum and archive, full of wonderful artefacts and exhibits — I especially loved the old photographs of life inside the Ark. It must have been incredible to be the earliest photographers to document the final years. Conservation work continues on the huge crumbling wall that encloses the it.

“And yet those ponds of Bukhara are wonderfully beautiful. In the evening, after the muezzin has sounded from the Minaret the call to prayer, the men of the city gather around the ponds, which are bordered by tall silver poplars and magnificent black elms, to enjoy a period of ease and leisure. Carpets are spread, the ever-burning chilim is passed from mouth to mouth, the samovar steams away, and lightfooted boys hand round the shallow bowls of green tea. Here the meddahs, or story-tellers, the musicians and the dancing boys assemble to display their craft. And perhaps a conjuror or a juggler comes, performing the most amazing and incredible feats of skill. An Indian snake charmer joins the throng and sets the poisonous snakes to dance, while all over reigns the peace of a Bukharan evening. No loud speech breaks the spell; items of scandal and the news of the day are exchanged in discreet whispers. So it was centuries ago in Bukhara, so it is today. There are things which not even the Soviets can alter.” — Alone Through the Forbidden Land by Gustav Krist, 1937.

11. A Special Meal of Plov in a Suzani Master’s Home

Our most special evening in Bukhara took place at the home of a suzani master. He and his wife prepared a traditional Uzbek plov (rice pilaf) for us, unparalleled in taste and far surpassing any other plov we had eaten before or since. It was full of fresh whole quince, onions, whole garlic bulbs, raisins, meat, and vegetables, and was simply ecstatically delicious. I could have eaten myself silly. We enjoyed our meal seated at a long table in a room full of new and old suzani pieces. I was especially taken by one old horse blanket suzani — can you imagine hanging such a piece of exquisite needlework on a horse?? I was on complete sensual overload.

After our meal, he brought out more suzani pieces and answered questions about his work. Two girls demonstrated embroidery stitches at a table in a corner, skeins of gorgeous silk thread hanging nearby. 200 embroiderers work for this suzani center now. The number of items for sale is staggering — all very high quality and correspondingly priced. Personally, given the amount of work and the workmanship represented in some of the best and largest pieces — one took an entire year to make and cost $15,000– I would consider them priceless. Greg mentioned that he brought a small group here last year who purchased altogether $10,000 worth of suzani one evening.

Similarly, we were introduced one afternoon to an Uzbek art professor and artist, who creates exquisitely detailed water colors of traditional and historical Bukharan scenes. Another day we visited the shop of a delightful, petite seamstress who makes custom silk ikat dresses and jackets — several of our group were measured in the morning, had a quick fitting in the afternoon, and their new clothes were delivered to the hotel at 7am the following morning. And one afternoon we stopped to meet a master metalsmith, who creates beautiful sewing scissors and pocket knives. We had lunch one day in a private home, where the wife made traditional delicious beet salad and featherlight homemade dumplings, and her husband told us about his grandfather — who had been the minister of education. In addition to family photographs, he brought out a beautiful map of Bukhara made by his grandfather about 100 years ago.

It is experiences like this that make me wish I could have spent a few more weeks in this country.

Onward to Samarkand

We drive from Bukhara to Samarkand along the same Silk Road route taken by the great armies of Alexander and Tamerlane. Our only stop is in Shakhrizabs (“Green City” — formerly called Kesh), 180 miles (4 1/2 hour drive) from Bukhara. Population 110,000, over 50% young people. It is one of the oldest cities in Central Asia and celebrates its 2715th anniversary this year! As we near the town, mountains with snow-covered peaks appear in the distance, like a mirage!

12. A Visit to the Birthplace of Tamerlane – Shakhrizabs

Tamerlane was born in Shakhrizabs in 1336, where he started out as a sheep-rustler, before becoming one of the greatest conquerors of all time. When the American diplomat Schuyler visited Shakhrizabs in 1873 he found 90 mosques and three madrassas, and noted that slavery was never allowed here. Even at executions, a criminal’s throat would be mercifully cut before he was hanged.

The Aksaray Palace was Tamerlane’s most grandiose project. The name means White Palace, symbolizing noble descent (not the color, which actually is a patterned combination of blue, green, and gold). Tamerlane brought artisans to Shakhrizabs to create the Palace’s ornate gateways, a domed reception hall with a gold ceiling, beautiful chambers and a banquet hall for his wives, water pools, gardens of fruit trees, a large complex. Even today its ruins are astonishingly huge — the towers are 200 feet high — and there is talk about trying to do some more restoration/preservation work. Starlings nest in its towers and make holes in the brick; water is eroding its structure — you can clearly see the damage outlined by deposits of salt on the bricks.

Written in huge letters above the entrance: “If you challenge our power, look at our buildings!”

Here also is the Mausoleum of Djakhangir, Tamerlane’s favorite and eldest son — who died at age 22 in 1375 after falling from a horse. Another son also was buried here in 1394. In 1404 the Spanish envoy visited the Mausoleum and noted that “Here daily by the special order of Timur [Tamerlane] the meat of twenty sheep is cooked and distributed in alms, this being done in memory of his father and of his son.”

Next door a simple mausoleum and crypt was constructed for Tamerlane, lined with slabs of limestone and sandstone, with a plain marble casket. It looks like a bunker with beautiful carved doors. One version of the story says that his wishes to be buried in this unadorned crypt were ignored; another version says he was displeased with the plainness of the mausoleum and ordered it destroyed. At any rate, the mausoleum was destroyed but the crypt remains — although the casket is empty. We climbed down the steep stone steps into the dark humid crypt and I immediately felt claustrophobic and hot. It did not seem particularly peaceful or even cool down there. Tamerlane is in fact buried in an ebony casket under a huge (the largest in the world) jade slab in Samarkand.

The nearby Kok Gumbaz (“Blue Dome”) mosque was built in 1437/8 by Ulug Beg, Tamerlane’s grandson, in honor of his father. It is impressive in its own right, but Tamerlane’s Aksaray Palace steals all my attention in all of its ruined glory. Even today, Tamerlane’s ferocious and insatiable rule impresses.

Samarkand (“Rich City” with 650,000 population today) was Tamerlane’s (14th century) capital city and the crossroads of Asia; it is located on the left bank of the river Zerafshan, surrounded on two sides by mountain ranges. All caravan trade routes passed through here. Tamerlane made sure it was the most powerful and beautiful city of all Central Asia. It had many names at that time: the Mirror of the World, the Garden of the Soul, the Jewel of Islam, the Pearl of the East, the Center of the Universe, City of Famous Shadows. It had not seen such prosperity since the ninth century, when under Samanid rule the streets were paved with stone, benefactors supplied iced water for free at some 2,000 locations, and an ingenious irrigation system of pipes fed every house and garden.

Today, Samarkand is a large, sprawling and surprisingly modern-looking city, completely different from Khiva and Bukhara. Modern shops line wide main avenues, trees everywhere.

The Bibi Khanym Mosque is named after Tamerlan’s favorite wife, a Chinese princess. Some say it was she who built it for him while he was off in India. Other accounts claim that Tamerlane himself vowed to create a mosque without parallel when he returned from sacking Delhi in 1398. Stories seem to agree, however, that skilled slave artisans were brought to Samarkand from all across the empire to build this mosque; and that almost one hundred elephants were imported from India to haul the heavy marble.

It is one of the largest mosques in the Islamic world. The vast dome is 135 feet high; the courtyard, 550 by 360 feet, where worshippers knelt and prayed, was floored in marble. It was designed to hold the entire male population of Samarkand for Friday prayers. A 60-foot arch is flanked by minarets 165 feet high. There were 400 marble pillars. In the middle of the courtyard is a stone pedestal, crafted from marble blocks, which was to serve as a stand for the huge Osman Koran. There is a tradition that women who wish to become pregnant should crawl around each of its nine thick legs. The detail here is extraordinary. Like so many other sites we have visited, it is too big to get your head around. One court historian of the time announced, “The dome would have been unique but for the sky being its copy; the arch would have been singular but for the Milky Way matching it.”

13. Visiting Registan

It had been a long day on the road but after dinner in the hotel garden we take a quick trip across town to see Registan Square all lit up at night. It is stunning.

Registan Square is Samarkand’s most famous landmark. It is among the greatest of all the grandiose works of the Islamic world. At first sight it appears that every surface is covered with mesmerizing patterns.

Its name means “Sandy Place,” and many claim that it got its name from the sand that was strewn on the ground to soak up blood from public executions, which were held there until the early 20th century.

The earthquake of 1932 caused the two main pillars to lean. Even after remediation, one of them is clearly leaning again. Fifteen years ago the Aga Khan donated $15 million to Uzbekistan for the restoration of the Registan, which was recently completed to reflect its original 14th century splendor. It is flanked by two beautiful public parks. By day it reflects the colors of desert and sky: sand, turquoise, gold. At night it glows.

In Tamerlane’s time it was the commercial and entertainment center of the town. Six roads ran through it. Military pageants, spectacles, and executions took place here.

The Square is edged by three magnificent madrassahs (Ulug Beg, Tillya-Kari, and Shir Dor). These were once centers of education with the finest scholars of the age in both Islamic and secular science; now these madrassahs house museums and souvenir shops. Gulya, our guide, takes us to visit several. In one, a musician demonstrates traditional Uzbek instruments; at another a professional restorer sells beautiful renderings on paper of design motifs from mosques and museums. Several walls are hung with beautiful old black and white photos of the Registan in earlier times. They are my favorites, but I have yet to find a collection of these available in book form.

The buildings themselves are stunning: huge facades and portals, domes, columns and minarets, all decorated with elegant designs in tiles glazed in green, yellow, turquoise, and blues, in geometric and floral motifs and Kufic calligraphy.

On the main portico of the Ulug Beg Madrassah, a 45-foot arch is covered with mosaic tiles depicting the sky and the stars. One inscription reads “This magnificent facade is of such a height it is twice the heavens and of such weight that the spine of the earth is about to crumble.”

And although figurative art is taboo in Islam, above one arch at the Shir D’or (meaning “Lion-Bearing”) is a remarkable sight: two lion-tigers with rising suns on their backs chase two white does through flowers and foliage. An inscription here reads “The skilled acrobat of thought climbing the rope of imagination will never reach the summits of its forbidden minarets.”

The Tillman-Kari madrassah completes the symmetry of the Square. Inside is an infinity of marble, and gold leaf.

Next to Registan Square is the Siyab Bazaar, Samarkand’s main bazaar, full of exotic spices, fruits, nuts, vegetables, household goods, and pushcarts full of rounds of unleavened bread called non (20 different varieties, each with its unique pattern). In the 10th century Samarkand produced 100 different kinds of grapes! Tea houses sit around the edges. It is a very busy place. Vendors encourage us to try free samples—and we are hooked. We buy fresh bread, halvah, almonds, apricots, strawberries, and share them around among our group.

14. Visit to the Ulugbek Observatory

Our last morning in Samarkand. We travel to a hill on the outskirts of the city, to see the Observatory of Ulugbek, the Gurkhani Zij. Ulugbek (Ulug Beg) was the astronomer king of the 15th century, Tamerlane’s grandson; he gathered mathematicians and astronomers here, drawing them from his madrassah in town. Using only a sextant, and long before the invention of the telescope, he studied the heavens, accurately positioned over 1,000 stars, discovered over 200 unknown stars, traced equinoxes and eclipses, worked out the exact tilt of the earth’s axis, and calculated the year to within a few seconds of that computed with modern electronics today (surpassing even the calculations of Copernicus). He produced the most detailed star catalog of his time, which was still known and studied in Oxford in the 17th century. A favorite quote from Ulug Beg, refreshingly heretical for its time: “Religions dissipate like fog, kingdoms vanish, but the works of scientists remain for eternity.”

I wish I could see it as it once was. The above-ground building itself was destroyed at the time of Ulugbek’s death; a new portal and vault stand now in its stead. However, the astonishing below-ground sextant is still intact.

I cannot describe it adequately in my own words, so will quote a guide: “It was the largest 90-degree quadrant the world had ever seen, though it is called a sextant as only 60 degrees were used. Deeply embedded in the rock to lessen seismic disturbance, the surviving 36-foot arc sweeps upwards in two marble parapets cut with minute and degree calibrations for the astrolabe [used to measure the tilt — the inclined position — in the sky of a celestial body] that ran its length. The arc completed its radius at the top of a three-story building. Above ground floor service rooms were arcades designed as astronomical instruments. A witness described the planetarium-like decoration: ‘inside the rooms he had painted and written the image of the nine celestial orbits and the shapes of the nine heavenly bodies, and the degrees, minutes, and seconds of the epicycles; the seven planets and pictures of the fixed stars, the images of the terrestrial globe, pictures of the climes with mountains, seas, and desserts…’” It must have been glorious. Also on site is an astonishing, beautiful museum about Ulug Beg and his observatory.

15. Visit to A Silk Paper Making Workshop

City workshops in Samarkand still produce rich silks, and metal, and for centuries its famous mulberry paper, the finest paper in the world. Chinese prisoners taught their art of paper making here in the 7th century. So we travel to Konigil, a small nearby village. Here, UNESCO has funded a new paper making workshop, and we spend time learning about the process, from the water mill that pounds the mulberry pulp to the naturally pink rough paper which is polished smooth by stone or seashell.

Farewell…

Our farewell lunch is served at this paper-making center. It is plov, of course, Uzbekistan’s national dish — this time a combination of beef and vegetables and apricots. Before lunch, we visit the outdoor area where the bread is baked. Following tradition, a fire is lit and kept burning until the insides of the oven turn white hot. The dough is shaped and then decorated with black sesame seeds and stuck on the sides of the oven to bake. Very ingenious.

We take the late afternoon train (an immaculate bullet train) to Tashkent and wait in a hotel until it is time to go to the airport. Our flight home leaves at 2:45am. With luck, we will be back home tomorrow by early evening.

I have felt very far from home on this journey. And very much a stranger, even though the Uzbek people have been so very welcoming to us—at times I have felt both completely in awe of and yet somewhat uncomfortable at the overwhelmingly grandiose scale of the history and architecture in this foreign Muslim world. Unlike Cambodia’s Angkor Wat, which is a huge museum-like ruin of a city, Uzbekistan’s historic cities contain restored complexes of immense scale that still breathe with everyday lives and carefully preserved relics. Even though I tried to prepare for this journey, I am aware that I cannot absorb and appreciate fully what I am witnessing. It seems unfair and inadequate to pass through so quickly, and somehow even a little disrespectful. Already I want to return. To be here at these crossroad cities of the famous Silk Road, at a time when master artisans are still available and active, is a rare gift.

If Lynda’s Blog has inspired you to travel to Uzbekistan, look at our Uzbekistan page and get in touch to talk to an expert to customize this tour for you and have all your questions answered.

For more details about any of our destinations, contact us: 800.633.1008 or 813.251.5355